Arya and Sansa

A Close Reading

“I wish we had more episodes,” he said, speaking from his home in Santa Fe, N.M. “I’d love to have 13 episodes. With 13 episodes, we could include smaller scenes that we had to cut, scenes that make the story deeper and richer.”

As for those missing moments, he cited a scene from the first novel, “A Game of Thrones,” that didn’t make it into Season 1. The Starks are traveling to King’s Landing, the capital of the Seven Kingdoms, with the royal family. The sisters Sansa and Arya Stark are invited to tea and lemon cakes with Queen Cersei, but Arya wants to go hunt for rubies with the butcher’s boy. And the sisters argue about it. Mr. Martin said he misses the scene because it adds texture and helps establish early on the characters of and relationship between the sisters.

Coming into this study, I didn’t expect to cross any passages that would merit close examination, and AGOT didn’t surprise me in that regard. But I wasn’t disappointed. I wanted to study Martin’s storytelling at a larger scale than the paragraph. Still, I want to do at least one close reading to give a sense of some of these narrative choices in context; since Martin made special mention of this scene, and this interviewer so kindly set it up for us, let’s slip it under the microscope. The scene begins:

She found Arya on the banks of the Trident, trying to hold Nymeria still while she brushed dried mud from her fur. The direwolf was not enjoying the process. Arya was wearing the same riding leathers she had worn yesterday and the day before.

ASOIAF is known for being readable, by which we usually mean “the plot really hums.” But it’s also a very easy read technically. Watch the sentence structures as we go – you’ll see a lot of simple or compound sentences. There’s a tradeoff here: basic sentences are easy to read, but you need more of them.

If you are not worried about your reader’s attention span, or are worried about page count, you can increase the density of your sentences. A clause with was as its main verb can usually be tucked into another sentence. Like so:

She found Arya on the banks of the Trident, in yesterday’s riding leathers, trying to hold Nymeria still while she brushed dry mud from her fur. The direwolf was not enjoying the process.

That’s 11 words shorter than Martin’s version, with only some loss of meaning and a change in rhythm. Not every paragraph can drop a quarter of its length, but many can, and over a seven book series this adds up.

To get the dataset for my dialogue analysis, I had to write a program that could guess at dialogue speakers. It’s pretty accurate, but I have to check it, which means that after carefully reading AGOT, I’ve been zipping through the other books. At the moment I’m a third of the way through ADWD, and to come back to a line like “The direwolf was not enjoying the process” – which is so light and domestic – sharply reminds me just how grim the series gets. Sandor looks like a monster, sure, but it’s the introduction of Rorge and Biter in ACOK that really opens the floodgates. Now I’m reading about Theon’s flayed fingers; but once we were grooming dogs!

“You better put on something pretty,” Sansa told her. “Septa Mordane said so. We’re traveling in the queen’s wheelhouse with Princess Myrcella today.”

“I’m not,” Arya said, trying to brush a tangle out of Nymeria’s matted grey fur. “Mycah and I are going to ride upstream and look for rubies at the ford.”

“Rubies,” Sansa said, lost. “What rubies?”

Arya gave her a look like she was so stupid. “Rhaegar’s rubies. This is where King Robert killed him and won the crown.”

This bit is a good example of how Martin gets us into Sansa’s head through free indirect. I talk more about that here.

Sansa regarded her scrawny little sister in disbelief. “You can’t look for rubies, the princess is expecting us. The queen invited us both.”

“I don’t care,” Arya said. “The wheelhouse doesn’t even have windows, you can’t see a thing.”

“What could you want to see?” Sansa said, annoyed. She had been thrilled by the invitation, and her stupid sister was going to ruin everything, just as she’d feared. “It’s all just fields and farms and holdfasts.”

In AGOT, Martin is not confident in how the dialogue will come offA skill he develops later, and that I talk about here, so he suggests line readings with his dialogue tags. Those last two boldings are examples of a venial sort of dialogue attribution. I evoke the language of sin because Stephen King hates dialogue attributions beyond “he said” and “she said.”That’s common advice, but I remember first seeing it in On Writing.

King would hate the next two lines for sure.

“It is not,” Arya said stubbornly. “If you came with us sometimes, you’d see.”

“I hate riding,” Sansa said fervently. “All it does is get you soiled and dusty and sore.”

Martin likes this scene because it establishes the contrast in the Stark sisters. Arya is the tomboy, Sansa the priss. You can see why this would get lost in the adaptation, because Martin is so consistent in setting up this opposition everywhere else in the book. Really this scene is an echo of the earlier scene in which Arya gets chastised for her poor sewing. But I understand why Martin wrote and likes the scene: the Stark diaspora is on the way, and the more scenes we can get with these people the better. First of all, it’s obviously a good thing to have your main characters interacting. The plot scatters the protagonists so widely that Dontos Hollard gets more face time with Sansa than Arya does. Secondly, we need some amity to sharpen the drama. Jon’s dilemma about helping Robb takes on weight when we have that moment in the yard when he sees the snowflakes melting in his brother’s hair.

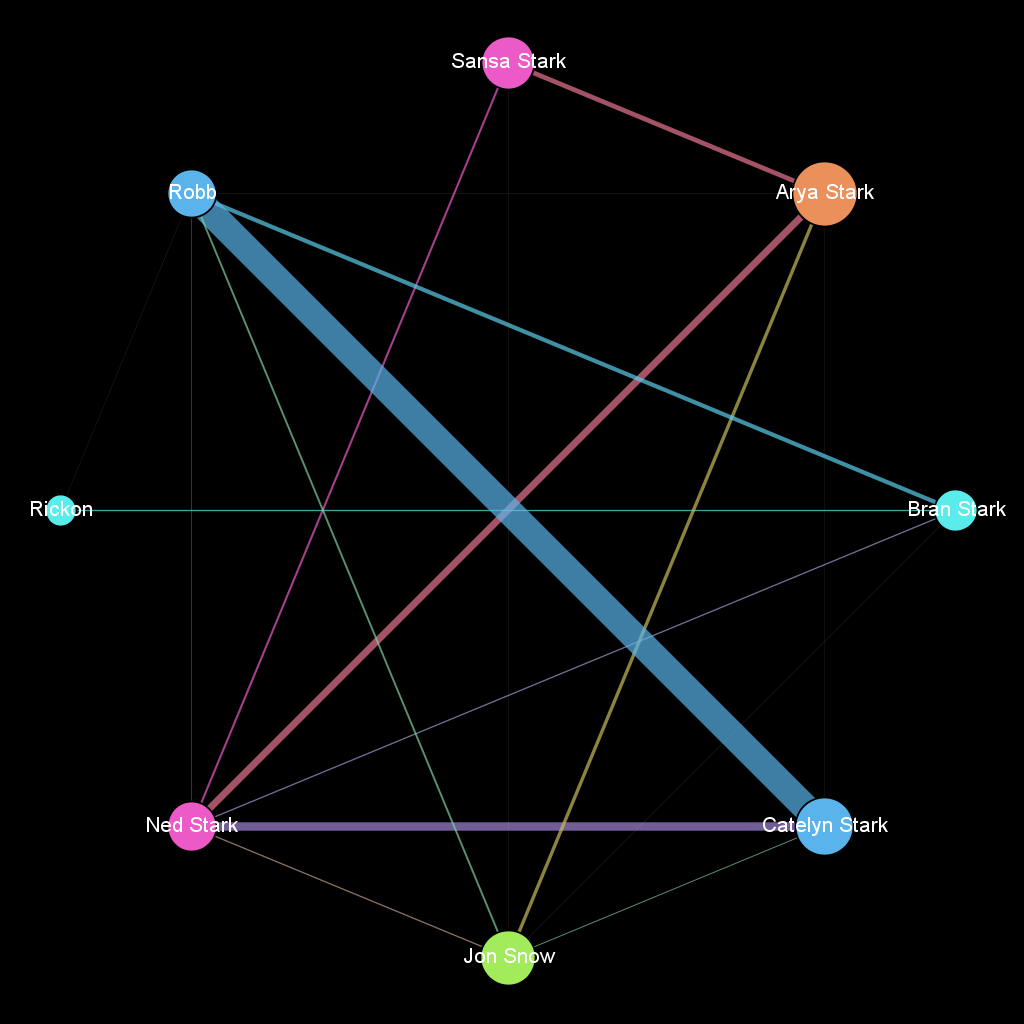

Check out this graph of the dialogue exchanges within the Stark family.

It’s not even a complete graph. Sansa, Bran, and Rickon never even got a word in with Catelyn before the Red Wedding. (Rickon hardly exists, to the point that you wonder if Martin wishes he’d never invented him. Then again, in a series with no qualms about kid-killing, he’s had plenty of opportunities to off him, which makes you suspect that the kid will have some part to play. Hard to say with Martin, which is of course how he likes it.)

Arya and Sansa have only 30 exchanges, 16 of which come from this scene.

Arya shrugged. “Hold still,” she snapped at Nymeria, “I’m not hurting you.” Then to Sansa she said, “When we were crossing the Neck, I counted thirty-six flowers I never saw before, and Mycah showed me a lizard-lion.”

I will never understand by what principle Martin selects his flora and fauna. Sometimes he invents species, other times he takes a real one. Crocodiles apparently don’t fit, but lions do. If it’s a question of how generic a word is, well he invents a tree called the sentinel, but also includes the pussywillow. This is an issue that I think about a lot, and I’m not sure anyone else does.

Sansa shuddered. They had been twelve days crossing the Neck, rumbling down a crooked causeway through an endless black bog, and she had hated every moment of it. The air had been damp and clammy, the causeway so narrow they could not even make proper camp at night, they had to stop right on the kingsroad. Dense thickets of half-drowned trees pressed close around them, branches dripping with curtains of pale fungus. Huge flowers bloomed in the mud and floated on pools of stagnant water, but if you were stupid enough to leave the causeway to pluck them, there were quicksands waiting to suck you down, and snakes watching from the trees, and lizard-lions floating half-submerged in the water, like black logs with eyes and teeth.

An uncommon passage of landscape description, successfully seen through Sansa’s filter. Though Martin doesn’t have much in common with Sansa, his treatment of her psychology seems to me the most distinctive of his POV characters. All the men sound roughly the same – more or less sardonic, more or less tortured by duty – but Sansa gets a separate treatment. Here it manifests in the breathless note of the last sentence, quicksand and snakes and lizard-lions, oh my.

None of which stopped Arya, of course. One day she came back grinning her horsey grin, her hair all tangled and her clothes covered in mud, clutching a raggedy bunch of purple and green flowers for Father. Sansa kept hoping he would tell Arya to behave herself and act like the highborn lady she was supposed to be, but he never did, he only hugged her and thanked her for the flowers. That just made her worse.

Then it turned out the purple flowers were called poison kisses, and Arya got a rash on her arms. Sansa would have thought that might have taught her a lesson, but Arya laughed about it, and the next day she rubbed mud all over her arms like some ignorant bog woman just because her friend Mycah told her it would stop the itching. She had bruises on her arms and shoulders too, dark purple welts and faded green-and-yellow splotches, Sansa had seen them when her sister undressed for sleep. How she had gotten those only the seven gods knew.

Arya was still going on, brushing out Nymeria’s tangles and chattering about things she’d seen on the trek south. “Last week we found this haunted watchtower, and the day before we chased a herd of wild horses. You should have seen them run when they caught a scent of Nymeria.” The wolf wriggled in her grasp and Arya scolded her. “Stop that, I have to do the other side, you’re all muddy.”

“You’re not supposed to leave the column,” Sansa reminded her. “Father said so.”

Arya shrugged. “I didn’t go far. Anyway, Nymeria was with me the whole time. I don’t always go off, either. Sometimes it’s fun just to ride along with the wagons and talk to people.”

Sansa knew all about the sorts of people Arya liked to talk to: squires and grooms and serving girls, old men and naked children, rough-spoken freeriders of uncertain birth. Arya would make friends with anybody. This Mycah was the worst; a butcher’s boy, thirteen and wild, he slept in the meat wagon and smelled of the slaughtering block. Just the sight of him was enough to make Sansa feel sick, but Arya seemed to prefer his company to hers.

The sisters’ difficult relationship pains Sansa, and not just because she thinks they should get along for appearance’s sake; there’s something in Sansa that she believes is essentially unlovable. Her insistence on courtesy and propriety is all part of an anxious performance of femininity, one she hopes will be so flawless that no one will ever glimpse her unworthiness. Arya’s scraped knees and nonchalant charisma – despite her plain looks and horsey grin – undermine Sansa’s entire project. Her insecurity is hinted at in the phrase “Arya seemed to prefer his company to hers,” which is wounded but trying hard to mask it with haughtiness. It’s a nice piece of writing.

This delicate touch has faded from the later books, probably because that’s the first thing to go when you’re constantly under deadline. Here’s a bit from a Sansa chapter in AFFC, which is so explicit it feels like the “Previously On” segment of a cable drama:

I am not your daughter, she thought. I am Sansa Stark, Lord Eddard’s daughter and Lady Catelyn’s, the blood of Winterfell. She did not say it, though. If not for Petyr Baelish it would have been Sansa who went spinning through a cold blue sky to stony death six hundred feet below, instead of Lysa Arryn. He is so bold. Sansa wished she had his courage. She wanted to crawl back into bed and hide beneath her blanket, to sleep and sleep. She had not slept a whole night through since Lysa Arryn’s death.