The Unseen Plane Crash: Psychic Distance

I’m a strong believer in telling stories through a limited but very tight third person point of view. I have used other techniques during my career, like the first person or the omniscient view point, but I actually hate the omniscient viewpoint. None of us have an omniscient viewpoint; we are alone in the universe. We hear what we can hear… we are very limited. If a plane crashes behind you I would see it but you wouldn’t. That’s the way we perceive the world and I want to put my readers in the head of my characters.

I’m going to drop a giant blockquote on you right off the top, but please don’t head for the exits yet. I think that if you want to talk about Martin as a writer, this concept is crucial. It’s called “psychic distance.”

John Gardner explains it in The Art of Fiction:

By psychic distance we mean the distance the reader feels between himself and the events in the story. Compare the following examples, the first meant to establish great psychic distance, the next meant to establish slightly less, and so on until in the last example, psychic distance, theoretically at least, is nil.

- It was winter of the year 1853. A large man stepped out of a doorway.

- Henry J. Warburton had never much cared for snowstorms.

- Henry hated snowstorms.

- God how he hated these damn snowstorms.

- Snow. Under your collar, down inside your shoes, freezing and plugging up your miserable soul…

When psychic distance is great, we look at the scene as if from far away—our usual position in the traditional tale, remote in time and space, formal in presentation (example 1 above would appear only in a tale); as distance grows shorter—as the camera dollies in, if you will—we approach the normal ground of the yarn (2 and 3) and short story or realistic novel (2 through 5). In good fiction, shifts in psychic distance are carefully controlled. At the beginning of the story, in the usual case, we find the writer using either long or medium shots. He moves in a little for scenes of high intensity, draws back for transitions, moves in still closer for the story’s climax. (Variations of all kinds are possible, of course, and the subtle writer is likely to use psychic distance, as he might any other fictional device, to get odd new effects. He may, for instance, keep a whole story at one psychic-distance setting, giving an eerie, rather icy effect if the setting is like that in example 2, an overheated effect that only great skill can keep from mush or sentimentality if the setting is like that in example 5. The point is that psychic distance, whether or not it is used conventionally, must be controlled.)

Martin does not always control psychic distance. He’s generally hovering right over his POV’s shoulders – in fact I think he’d prefer to crawl in their heads if he could justify 15 different I’s – only to take a big step backwards at odd times. Tyrion and Jaime are at breakfast here:

Cersei stood abruptly. “The children don’t need to hear this filth. Tommen, Myrcella, come.” She strode briskly from the morning room, her train and her pups trailing behind her.

Jaime Lannister regarded his brother thoughtfully with those cool green eyes. “Stark will never consent to leave Winterfell with his son lingering in the shadow of death.”

“Pups” sounds like a term Tyrion would use, but Tyrion wouldn’t call his brother Jaime Lannister, or refer to himself as the brother of Jaime Lannister – that’s Martin talking.

In this next quote, who thinks Jon is being stupid? Jon, or the narrator?

Stupidly, Jon argued. “I’ll be fifteen on my name day,” he said. “Almost a man grown.”

Another one with Jon:

Jon could taste the mockery there, but there was no denying the truth. The Watch had built nineteen great strongholds along the Wall, but only three were still occupied: Eastwatch on its grey windswept shore, the Shadow Tower hard by the mountains where the Wall ended, and Castle Black between them, at the end of the kingsroad. The other keeps, long deserted, were lonely, haunted places, where cold winds whistled through black windows and the spirits of the dead manned the parapets.

Jon’s never been to any of these places, and the ghosts on the parapets is a little poetic anyway.

When Viserys gets crowned by Drogo, some of the future leaks in:

Viserys smiled and lowered his sword. That was the saddest thing, the thing that tore at her afterward… the way he smiled.

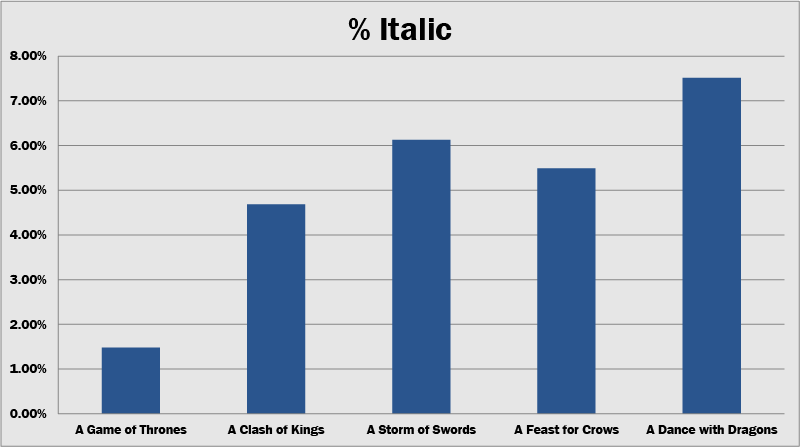

Martin’s accuracy at the various distances is fine to good, though I’ve never liked his closest work, represented by all that italicized interior monologue. It’s never been necessary, and there’s more of it with every book.

(Disclaimer: I am assuming that the proportion of italicized text belonging to interior monologue is somewhat consistent across the books. Text may be italicized for other reasons: to emphasize dialogue, or indicate a foreign term like cyvasse.)

You might shrug at those proportions. Is a 6 percent increase that big a deal? Absolutely, particularly when those italicized bits are Martin at his kludgiest. He uses them to jog the reader’s memory, wedge in a pile of backstory, or point out the obvious.

Here we join Jon right after he receives the news of King Robert’s death and his father’s imprisonment:

A north wind had begun to blow by the time the sun went down. Jon could hear it skirling against the Wall and over the icy battlements as he went to the common hall for the evening meal. Hobb had cooked up a venison stew, thick with barley, onions, and carrots. When he spooned an extra portion onto Jon’s plate and gave him the crusty heel of the bread, he knew what it meant. He looked around the hall, saw heads turn quickly, eyes politely averted.

So we get the idea: word’s gotten out that Jon’s dad is accused of treason. But I actually cut out two bits from the paragraph. Here it is in full:

A north wind had begun to blow by the time the sun went down. Jon could hear it skirling against the Wall and over the icy battlements as he went to the common hall for the evening meal. Hobb had cooked up a venison stew, thick with barley, onions, and carrots. When he spooned an extra portion onto Jon’s plate and gave him the crusty heel of the bread, he knew what it meant. He knows. He looked around the hall, saw heads turn quickly, eyes politely averted. They all know.

The emphasis is Martin’s. Two of the many pieces of transcribed thoughts in the book. Did they add anything to that paragraph?

This chapter is particularly afflicted with gratuitous thoughts. When they find some dead bodies beyond the Wall:

He turned the corpse over with his foot, and the dead white face stared up at the overcast sky with blue, blue eyes. “They were Ben Stark’s men, both of them.”

My uncle’s men, Jon thought numbly.

They go back to Castle Black:

As they led their horses back to the stable, Jon was uncomfortably aware that people were watching him. Ser Alliser Thorne was drilling his boys in the yard, but he broke off to stare at Jon, a faint half smile on his lips. One-armed Donal Noye stood in the door of the armory. “The gods be with you, Snow,” he called out.

Something’s wrong, Jon thought. Something’s very wrong.

Jon gets the bad news, and worries about his sisters:

The rest of the afternoon passed as if in a dream. Jon could not have said where he walked, what he did, who he spoke with. Ghost was with him, he knew that much. The silent presence of the direwolf gave him comfort. The girls do not even have that much, he thought. Their wolves might have kept them safe, but Lady is dead and Nymeria’s lost, they’re all alone.

He freaks out on Aliser Thorne and gets thrown in the brig, but there’s trouble in the night:

His guard was sprawled bonelessly across the narrow steps, looking up at him. Looking up at him, even though he was lying on his stomach. His head had been twisted completely around.

It can’t be, Jon told himself. This is the Lord Commander’s Tower, it’s guarded day and night, this couldn’t happen, it’s a dream, I’m having a nightmare.

That’s probably the worst of it from AGOT, but as the use of italics increases, these clunkers become easier to find.

Here’s Catelyn reviewing her history with the Stark boys:

I gave Brandon my favor to wear, and never comforted Petyr once after he was wounded, nor bid him farewell when Father sent him off. And when Brandon was murdered and Father told me I must wed his brother, I did so gladly, though I never saw Ned’s face until our wedding day. I gave my maidenhood to this solemn stranger and sent him off to his war and his king and the woman who bore him his bastard, because I always did my duty. (ACOK)

If this was a monologue from Catelyn’s one woman show, fair enough, but in context it stands out as a bald intrusion of backstory.

Other excerpts highlight the imperfect fit with the other narrating voices. This one, from the epilogue of ASOS, is particularly jarring.

Merrett hated the woods, if truth be told, and he hated outlaws even more. “Outlaws stole my life,” he had been known to complain when in his cups. He was too often in his cups, his father said, often and loudly. Too true, he thought ruefully. You needed some sort of distinction in the Twins, else they were liable to forget you were alive, but a reputation as the biggest drinker in the castle had done little to enhance his prospects, he’d found. I once hoped to be the greatest knight who ever couched a lance. The gods took that away from me. Why shouldn’t I have a cup of wine from time to time? It helps my headaches. Besides, my wife is a shrew, my father despises me, my children are worthless. What do I have to stay sober for?

It sounds to me like the narrator and Merrett are conversing. A distant narrator, lacking access to Merrett’s inner monologue, might hint at it with a line like

“Outlaws stole my life,” he had been known to complain when in his cups. He was too often in his cups, his father said, often and loudly.

But then Merrett agrees, Too true. The italics suggest that this is reported speech. The next sentence is romanized, so we’re now at a remove from him, though not too far, considering the you… but then there’s a long italic monologue. Is this also reported speech? Are we to understand that Merrett is thinking all these things about his hopes and his shrew wife? Either way, the text’s awareness of the reader is distracting. I understand why Martin would do it. We’ve never met Merrett before, and he’ll be dead in five pages, so Martin’s got to engage our interest as quickly as possible. But I’m also aware of all these motivations as I’m reading.

In both cases my real complaint is with the italicized I. I don’t know about you, but I don’t review my autobiography while I’m going about my day. The frustrating thing is that there’s a way to do that without reported thoughts: third person! It’s absolutely standard for a narrator to tell us something like Cat’s monologue, and it doesn’t seem phony because it makes no pretense of quotation. The reader understands that these sentences aren’t intercepted on the psychic CB, but rather representative of the kind of headspace the character is in.

Let’s consider two more scenes in which the psychic distance is more skillfully handled. The first is Ned’s resignation as Hand.

This chapter launches with a debate about whether or not Dany can be allowed to live. The Honorable Gentlemen Ned Stark and Barristan Selmy refuse to cosign an assassination, and Ned turns in his badge to prove he’s serious. He returns to his quarters and tells his steward that the Stark presence in King’s Landing will be coming to an end, quick. But he has misgivings.

The following shows how you can do an internal debate, which I find much trickier than the explicit debate that opened up the chapter. As you would expect, Martin gets very close with the psychic distance.

When he had gone, Eddard Stark went to the window and sat brooding. Robert had left him no choice that he could see. He ought to thank him. It would be good to return to Winterfell. He ought never have left. His sons were waiting there. Perhaps he and Catelyn would make a new son together when he returned, they were not so old yet. And of late he had often found himself dreaming of snow, of the deep quiet of the wolfswood at night.

Those oughts mean we’re way into Ned’s head; disembodied narrators don’t tell their characters what they should do. Interesting that Martin first refers to Ned as “Eddard Stark,” a marker of narrative distance. It works here because of that verb, brooding. In the first sentence we are presented with the inscrutable image of a man at a window. But hold on, aren’t we reading a book? So Martin opens the door of Ned’s mind and waves us in; the enjoyment of this access is heightened a little by the initial aloofness.

And yet, the thought of leaving angered him as well. So much was still undone. Robert and his council of cravens and flatterers would beggar the realm if left unchecked… or, worse, sell it to the Lannisters in payment of their loans. And the truth of Jon Arryn’s death still eluded him. Oh, he had found a few pieces, enough to convince him that Jon had indeed been murdered, but that was no more than the spoor of an animal on the forest floor. He had not sighted the beast itself yet, though he sensed it was there, lurking, hidden, treacherous.

In a third-person story, I’m not sure you can get any closer to a character’s thoughts. This starts to sound almost like a soliloquy, with highly verbal speech markers, like the ellipsis or the “Oh, he had…”

Notice also that Martin uses the hunting metaphor. Writing must always be concrete, our language isn’t well equipped for meta-cognition. So Ned thinks about current and future actions: sons waiting, have another kid, the realm will be beggared, etc. And when he’s talking about his more abstract failure to solve the Arryn mystery, the hunting metaphor gives us something to see, even though Ned is just sitting at the window.

It struck him suddenly that he might return to Winterfell by sea. Ned was no sailor, and ordinarily would have preferred the kingsroad, but if he took ship he could stop at Dragonstone and speak with Stannis Baratheon. Pycelle had sent a raven off across the water, with a polite letter from Ned requesting Lord Stannis to return to his seat on the small council. As yet, there had been no reply, but the silence only deepened his suspicions. Lord Stannis shared the secret Jon Arryn had died for, he was certain of it. The truth he sought might very well be waiting for him on the ancient island fortress of House Targaryen.

And when you have it, what then? Some secrets are safer kept hidden. Some secrets are too dangerous to share, even with those you love and trust. Ned slid the dagger that Catelyn had brought him out of the sheath on his belt. The Imp’s knife. Why would the dwarf want Bran dead? To silence him, surely. Another secret, or only a different strand of the same web?

Now Ned starts to question himself, another sure sign of close psychic distance.

Could Robert be part of it? He would not have thought so, but once he would not have thought Robert could command the murder of women and children either. Catelyn had tried to warn him. You knew the man, she had said. The king is a stranger to you. The sooner he was quit of King’s Landing, the better. If there was a ship sailing north on the morrow, it would be well to be on it.

Martin italicizes speech for a few reasons. Typically, italicized phrases tell us that the character is talking to him/herself, as with that “And when you have it…” But Catelyn’s warning, a spoken line of dialogue from the past, also gets italics. And that’s the key: italics are reserved for the words heard but unspoken. That could be remembered dialogue, or unsaid dialogue:

“Robert…” Joffrey is not your son, he wanted to say, but the words would not come.

Let’s move on to a scene with Sansa, a POV who has no power and therefore has to be interesting as a narrator. We watch the first day of the Hand’s Tourney from deep behind the starfield of her eyes, and Martin inflects the narrative with Sansa’s perspective without ever lapsing into those annoying italic monologues.

Jeyne covered her eyes whenever a man fell, like a frightened little girl, but Sansa was made of sterner stuff. A great lady knew how to behave at tournaments. Even Septa Mordane noted her composure and nodded in approval.

In these three sentences we see three different ways to keep psychic distance close.

1.) Value judgements. The narrator isn’t calling Jeyne a frightened little girl (though she is one!), that’s Sansa playing at being tough, and we know it because she then puffs herself up by thinking I am made of sterner stuff.

2.) The cultural code. I’m referring to one of the six codes of meaning that Barthes talks about in S/Z, and this is the one that refers to a body of knowledge – for Sansa, the rules of chivalry. Prescriptions like “A great lady knew how to behave at tournaments” makes a claim to objectivity – this is the way the world is – but of course it’s wildly subjective, because it does not describe, but prescribes.

3.) Even. If you take that from the third sentence, we’re not sure if Sansa notices the noticing. But even assures us she does. Why? Even is being used as an intensifier, like very and really, and objective narrators rarely use those. Is there something about intensifiers that automatically disqualifies a sentence containing one from belonging to the objective narrator? I don’t think so. It’s just a useful convention, one more way for writers to mark psychic distance and create subjective voice.

I think Martin is at his best when he’s working in this near-middle distance. When he strays from it, the writing can become purple (when he gets too far) or clumsy (when it gets too close).

As handy as close psychic distance can be, writers get restive. Some types of description don’t seem right in that mode. Here, Martin wants to needle Sansa a bit for being so swept up in Lorasmania, so we slip out of her headspace for a paragraph.

His last match of the day was against the younger Royce. Ser Robar’s ancestral runes proved small protection as Ser Loras split his shield and drove him from his saddle to crash with an awful clangor in the dirt. Robar lay moaning as the victor made his circuit of the field. Finally they called for a litter and carried him off to his tent, dazed and unmoving. Sansa never saw it. Her eyes were only for Ser Loras. When the white horse stopped in front of her, she thought her heart would burst.

There you go: Sansa doesn’t even notice poor Robar Royce being carted off. But he could have communicated this without widening out the psychic distance. Maybe something like:

… and drove him from his saddle to crash with an awful clangor in the dirt. While Robar lay moaning, Loras spurred his white mare into a smooth trot. The gallery’s cheers followed him in a wake as he made his victory lap, visor up and lance high. He had to rein up briefly – some men with a litter were hustling towards the center of the field – but soon the white horse stopped and pawed the dirt before Sansa, and she thought her heart would burst.

Grant me the absurdity of a self-published writer saying “No, no, like this” to an author who has sold millions. I think that keeping Sansa’s focus locked on Loras, and having the medics appear only as a distraction dismissed within a single parenthetical, keeps us within Sansa’s POV and still makes a point about her starry-eyed obliviousness.

But all of the foregoing analysis raises a big question: is it actually a problem to move the psychic distance?

To go back to Gardner, yes. Right before he explains the concept, he writes:

Careless shifts in psychic distance can also be distracting […] A piece of fiction containing sudden and inexplicable shifts in psychic distance looks amateur and tends to drive the reader away.

The most sudden and inexplicable shift of this sort is in the book’s very last chapter. Martin actually leaves Dany’s headspace and the past tense to deliver a paragraph of pure narratorial exposition in the present.

“I will,” Dany said, “but it is not your screams I want, only your life. I remember what you told me. Only death can pay for life.” Mirri Maz Duur opened her mouth, but made no reply. As she stepped away, Dany saw that the contempt was gone from the maegi’s flat black eyes; in its place was something that might have been fear. Then there was nothing to be done but watch the sun and look for the first star.

When a horselord dies, his horse is slain with him, so he might ride proud into the night lands. The bodies are burned beneath the open sky, and the khal rises on his fiery steed to take his place among the stars. The more fiercely the man burned in life, the brighter his star will shine in the darkness.

Let’s remember that opening quotation: “I have used other techniques during my career, like the first person or the omniscient view point, but I actually hate the omniscient viewpoint.”

For another good example of shifting psychic distance, here’s a scene in which Martin cycles through every possible nomination for Ned.

Her father had been fighting with the council again. Arya could see it on his face when he came to table, late again, as he had been so often. The first course, a thick sweet soup made with pumpkins, had already been taken away when Ned Stark strode into the Small Hall. […]

“My lord,” Jory said when Father entered. […]

“Be seated,” Eddard Stark said.

We’re in a Sansa chapter, and in Sansa/Arya chapters Ned goes by “her father” or “Father”. It’s distracting to see it every other way.

Tyrion sighed. “Look at me, Pod […] Who is inside my solar?”

“Lord Littlefinger.” Podrick managed a quick look at his face, then hastily dropped his eyes. “I meant, Lord Petyr. Lord Baelish. The master of coin. “

“You make him sound a crowd.”