Each week in the writing workshop, one student would choose a story for the rest of the class to read and discuss. The teacher had just one stipulation: no sci-fi or fantasy, please. When a guy who wrote about wizards protested, she patiently explained that, in her experience, both genres were trash. (I’m paraphrasing.)

So when it was my turn to pick a story, I defiantly xeroxed two dozen copies of M. John Harrison’s “Egnaro.” I brought them in and passed them out. Before stuffing the printout in her bag, the professor squinted at the title, perhaps suspecting my minor protest. But she didn’t recognize Harrison’s name.

You may not either. Though he’s had a long and successful career (winning the Tiptree and the Arthur C. Clarke awards), he’s still more likely to be your favorite sf/f author’s favorite author than yours. That was the case for me in 2006, when I picked up Viriconium in a Borders because Neil Gaiman had written a foreword for it. (Borders and Neil Gaiman: two relics of the mid-aughts for you, right there.) It turned out that Gaiman had made the classic mistake of introducing a new acquaintance to his cooler friend; by about page 80 Gaiman had been supplanted, and it was Viriconium — not American Gods — that made the trip out to college with me, to soon be joined by the collection Things that Never Happen, which includes “Egnaro.” But would my professor, who wrote down-the-middle literary fiction, see in Harrison what I did?

When class reconvened the next week, she asked us to take out our copies of “Egnaro”, and then kicked us off with a judgment of Harrison that I will borrow for the same purpose:

“He writes really rigorous sentences.”

Throughout this study we will try and figure out how to get some of that rigor in our own work. I encourage you to skip around as you like or as you get bored: each analysis can be read on its own, and if there are any dependencies I’ll be linking to them. I’ve starred the most valuable essays if your scrolling finger gets weary. Oh, and if you don’t remember the Viriconium stories that well, that’s fine — we’re focusing on prose, not plot.

Some Kinda Something

If every genre is a box, stuffed full of tropes, props, and stock characters, there are also some fundamental attitudes in there, holding the rest in place like packing peanuts. Science fiction has space ships and aliens nestled amongst an interest in the future, the boundaries of humanity, the promise & peril of technology, etc. Fantasy has swords and sorcery wrapped lovingly in nostalgia for a time before all of... this.

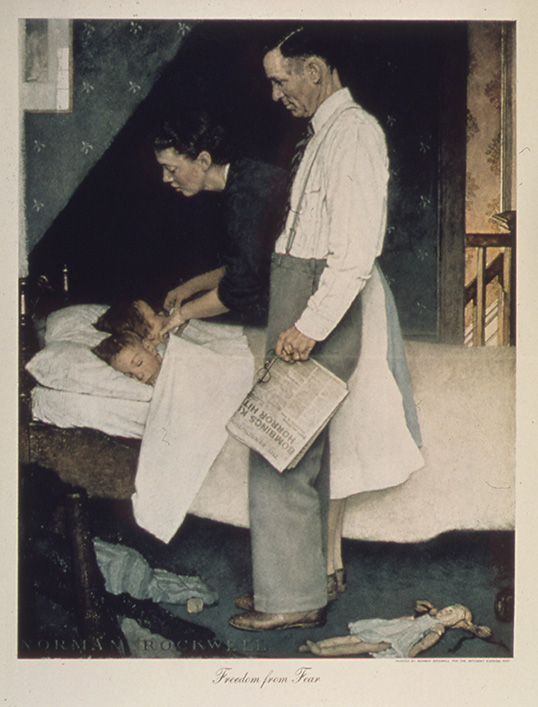

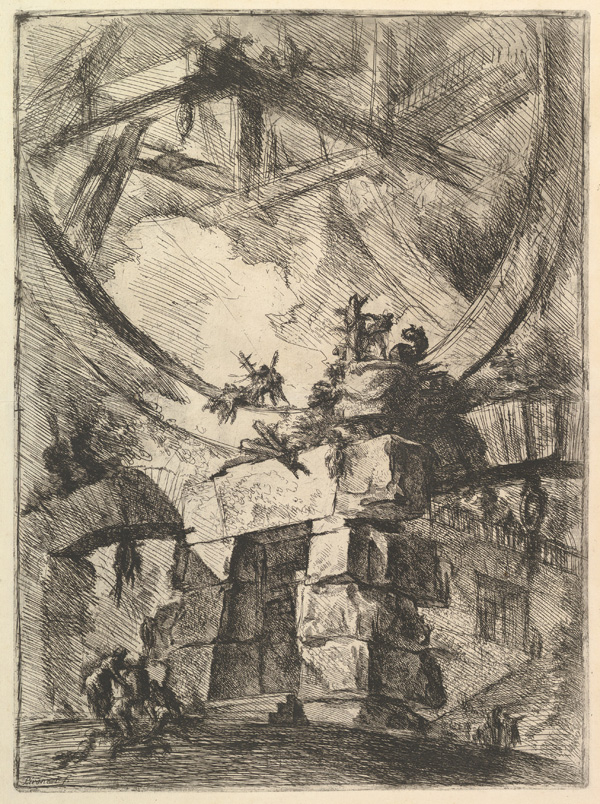

Because there was a time before this, right? Before high fructose corn syrup, social media, melting ice sheets, and a rolling wave of extinctions, there must have been some innocence to be had. Put simply, fantasy often wants the childlike ignorance enjoyed by those kids in the Rockwell painting, "Freedom from Fear": tucked into bed while their father looks on, holding a newspaper full of terrible headlines from the second World War. But if ignorance can produce a charming naïveté, there is also its reverse: the childlike horror of not understanding the world around you. Dying Earth stories, a subgenre to which Viriconium belongs, like to tap into this feeling. Viriconium occupies a moment in which humanity is playing in the boneyard of the gods. Wondrous technologies and remnants of bizarre catastrophes litter the landscape, obscure and blankly threatening.

Some seventeen notable empires rose in the Middle Period of the Earth. These were the Afternoon Cultures. All but one are unimportant to this narrative, and there is little need to speak of them save to say that none of them lasted for less than a millennium, none for more than ten; that each extracted such secrets and obtained such comforts as its nature (and the nature of the universe) enabled it to find; and that each fell back from the universe in confusion, dwindled, and died. The last of them left its name written in the stars, but no one who came later could read it. More important, perhaps, it built enduringly despite its failing strength—leaving certain technologies that, for good or ill, retained their properties of operation for well over over a thousand years. And more important still, it was the last of the Afternoon Cultures, and was followed by Evening, and by Viriconium.

You can see how the narrator denies you the specifics of these precursor cultures. The stated reason — they are unimportant to this narrative — is perfectly true, but it’s important that they be unimportant. By which I mean, there would be something reassuring about getting a detailed chronology of everything that led to Viriconium. We would have a sense of how we got here. That doesn’t suit Harrison’s purposes. Instead he lets us know that our story is taking place after the doom of all these sci-fi wonders, and here we are, post-Evening — and I don’t think we’re meant to infer that Viriconium represents the Dawn.

Harrison maintains this cryptic, slightly sinister vagueness throughout. So you will see many sentences gesturing towards the indescribable, the unimaginable, the equivocal, the mysterious, and the weird.

A dim, disturbing phosphorescence of fluctuating colour hung over the mere and its environs; caused by some strange quality of the water there, it gave an even but wan light.

Refugees packed the Viriconium road like a torchlit procession in some lower gallery of Hell.

He retained the impression of something fading, of a noise he had never actually heard gradually diminishing from some unimaginable crescendo [...]

It had been formed in some unimaginable past from a single obsidian monolith two hundred feet long by seventy or eighty in diameter; raised on its end by some lost, enormous trick of engineering; and fused smoothly at its base into the bedrock of the island.

Much later, when an irreversible process of change had hold of them both, he was to learn her name — Fay Glass, of the House of Sleth, famous a thousand and more years ago for its unimaginably oblique acts of cruelty and compassion.

Privately they call this twilight country of perception “the margins,” and some believe that by committing themselves wholly to it they will in the end achieve not only a complete liberation from linear Time but also some vast indescribable affinity with the very fabric of the “real.”

It was plain that the air of earth could not support so gross a body — he wallowed rather in some mysterious water glass, some dimension of his own.

Its voice faded into an enormous echoing distance in which might be heard quite distinctly the sound of waves on some unimaginable shore.

Power plants enfeebled by its unimaginable journeys, substructure creaking like an old door, it nevertheless wriggles ecstatically under his hands, light flaring off its stern.

Faster and faster the tears welled up over his chapped knuckles, until they were a rivulet — a torrent — a waterfall which splashed down his barrel chest, cascaded over his feet, and rushed off into an unimaginable outer darkness, cleansing the god in him of the reek of dead fish and stale wine, of all the filth he had accumulated during his long sojourn in the city.

It was a land of immense, barely populated glacial moors, flanked by the tall hills — of bogs and peat streams — of granite boulders split from the Mountains of Monar during slow, unimaginable catastrophes of ice, deposited to wear away in the beds of wide, fast, shallow rivers;

This sense of threatening ambiguity applies to the characters as well. My next study is of George R.R. Martin, and his characters run like clockwork. They have certain traits and certain histories that determine their responses to any event. This determinedness is part of what makes them so fun, because the reader has a strong sense of what they will do, which Martin then exploits for twists and character growth.

Harrison’s characters are not determined in this way. Their histories are patchy or altogether omitted, and their actions bubble up from unexplained bits of their psyche. They do things without understanding their own motives. I think this is the most realistic thing about Harrison, and I think this puts off a lot of readers. Leaving beside the possibly unpleasant reading experience of these unpredictable characters, there is a challenge to the reader’s worldview here. Does your outlook allow for people with empty space inside of them, who do not obey the classical mechanics of emotion?

The face of Methvet Nian hung before him, in the grip of some deep but undefinable sorrow.

Steadily though, as if he were leaving the haven of some second childhood, even these reference points seemed to be withdrawn from him, to be replaced by a rushing chaos, the sense of an act of memory continually performed without relief, a hidden river in the night, from which might sometimes surface unbidden some fragment of an event drifting like a dead branch amid the unidentifiable rubbish of the tides.

Since his triumphant entry at the head of the Reborn Armies eighty years ago (the Northern wolves driven before him to be caught at last between his hammer and the anvil of Tomb the Giant Dwarf), he had gone about Viriconium like the courier of a god, the very beat of his heart a response to some lost prehistoric cue.

Out of some strange sentiment, he had left the light burning in the upper room.

At the prompting of some impulse he did not quite understand, Cromis had rescued the corpse of Cellur’s bird from the ship.

It came very close to his, twitching and dissolving under the impact of some deeply felt emotion, then retreated with a hiss of indrawn breath.

He drew his knife and, in an access of some emotion he did not quite recognise, went off shouting up the hill and was ambushed and killed among the gravestones.

Here’s Harrison’s rationale for this method of characterization.

To go back to Katherine Mansfield: if you just present the events to the reader (or appear to), then the complexity of human motive will spin off that. If you try too hard to determine the way the reader sees character and motivation, you will actually restrict the reader’s interpretive opportunities. By limiting the amount of guidance you give, you automatically get the depth and complexity of interpretation you want. Because that’s what we readers do in real life — we interpret people’s actions and thus assign them “motive” and “character.” (From his interview with Strange Horizons)

Pathetic Fallacy

The pathetic fallacy, or “the attribution of human feelings and responses to inanimate things or animals,” is only a fallacy to the most literal of people.

(Weird sidenote about the term’s coiner, the 19th-century art critic John Ruskin: his Victorian sensibilities were so rattled by the sight of his naked bride on their wedding night that he sought an annulment. I get the sense there’s more to that story. Source)

For readers with a tolerance for figurative language, the pathetic fallacy is a welcome device. Harrison uses it frequently, I think because it lets him set a mood without having to climb behind the characters’ eyes. He prefers to narrate from a remove, and indicate psychology more obliquely. The pathetic fallacy may compensate for this distance by introducing subjectivity in unexpected places.

Wind, sky, stars and houses are personified in the examples below. See if you like it.

He came to Bread Street at twilight. It was far removed from the palace and the Pastel Towers, a mean alley of aging, ugly houses, down which the wind funneled bitterly. Over the crazed rooftops, the sky bled. He shivered and thought of the Moidart, and the note of the wind became more urgent. He drew his cloak about him and rapped with the hilt of his sword on a weathered door.

April again. When the sun goes in, a black wind tears the crocus petals off and flings them down the ring road.

It had no windows. He could not guess its intended purpose, or why it was not built of native stone. It stood enigmatically among its own rubble, an eroded stub,

He grinned painfully at the ironical shards of his own blade, winking up at him from the cracked flags, each one containing a tiny, perfect reflection of the mad retreating figure of the balladeer, coxcomb flapping in the homicidal night.

The Name Stars glittered cynically, commemorating some best-forgotten king.

Cowed by geography, Time, and the sea, its lime-washed cottages huddle uneasily amid a greater architecture; above them a road has been pushed through the rotting slates, and winds its way perilously up to the clifftop pastures.

A few houses stare morosely at it from the city side of the canal.

Shadows danced crudely, black on the black walls.

Zeugma

Zeugma is all over prose narratives. I use the term pretty loosely, referring to any of the four types outlined on the Wikipedia page, but in The Pastel City Harrison uses the most noticeable type, type 2.

Zeugma (often also called Syllepsis, or Semantic Syllepsis): where a single word is used with two other parts of a sentence but must be understood differently in relation to each. This is also called “semantic syllepsis.” Example: “He took his hat and his leave.” (wikipedia)

Here’s how Harrison uses it.

She offered him cheap, artificially coloured wine. They sat on opposite sides of a table and a silence.

The doors of the inn were wide open, spilling yellow light into the blue and a great racket into the quiet square.

To his left, Tomb the Dwarf towered above the Northmen in his exoskeleton, a deadly, glittering, giant insect, kicking in faces with bloodshod metal feet, striking terror and skulls with his horrible axe.

These drop out in the later Viriconium stories, perhaps for being too flashy. But the figure persists in a more subtle form.

To be is a ubiquitous and unexciting verb, making it a prime candidate to be hidden by authors. Say I need to describe a person. I want to observe that “his arms were like sticks” and “his rib cage was huge”. Run consecutively, they don’t feel great:

His arms were like sticks, and his rib cage was huge.

Or:

His arms were like sticks. His rib cage was huge.

Zeugma gives us an alternative that is both compact and rhythmic:

His arms were like sticks, his rib cage huge.

For context, there are 9,799 non-dialogue sentences in the Viriconium book, and I found this particular structure 21 times. That should give you an idea of just how varied sentences can be; before I did the tally, I thought, “Wow, Harrison really leans on this structure!” Well, not quite. I’m intrigued at how the structure seems to imply the content for him (or vice versa) — lot of talk about air in here.

The reforged sword was cooling, the furnace powered-down, the brigands noisily asleep or dozing in their smelly blankets.

The estuary was filled with a brown, indecisive light, the island dark and ill-defined, enigmatic.

They were a grim, rough-handed crew, with wind-burnt faces and hard, hooded eyes; their speech was harsh, their laughter dangerous, but their weapons were bright and well-kept, and the coats of their mounts gleamed with health over hard muscle.

Her face was set, the lips tight.

Her eyes were phlegmatic, her arms full of greengrocery.

Their faces were waxy with despair, their eyes like lemurs’.

Her eyes were a deep, sympathetic violet colour, her hair the russet of autumn leaves.

His features were bland and boneless, his skin unwrinkled but of a curiously dry, aged texture.

His throat was bare, the skin smooth and olive-coloured.

The water was corrupted and undrinkable, the paths difficult to find.

When he looked up again the city was lost, the evening grey and chilly, and an old man in a long cloak was walking up the path towards him.

He was the enigma of the Low City, the meat and drink of their gossip.

It was quiet, the streets empty and stunned.

The air was warm, the valley dappled with honey-coloured light.

The air was bitter inside the nose, the sky as black as anthracite.

The city was unseasonably dank again, the air chilly and lifeless.

Within the tall brick walls — which, with their mats of bramble, bladder senna, and reddish ivy, dulled the sounds of construction coming from either side — the air was sharp and rapturous, the light a curiously bleached lemon colour.

The pack animals were fractious, the wind bitter.

The horses were skittish from lack of exercise, the tunnels ill-lit.

Its limbs were thick and heavy, its head a blunted ovoid, featureless but for three glowing points set in an isosceles triangle.

As If

“As if” can be used a few different ways. Sometimes it signals a simile that includes a verb phrase. Other times it is the launch point for a flight of fancy. Coetzee, subject of my last study, doesn’t use the construction much. When he does, he is quite reasonable with his comparisons. Let’s see some of those:

It is as if the ghost of her cousin still lurks, calling her back to the dark kitchen to complete what she was writing to him.

Then at midday the wind drops as suddenly as if a gate has been closed somewhere.

I look into his clear blue eyes, as clear as if there were crystal lenses slipped over his eyeballs.

Harrison uses “as if” frequently and quirkily. Some of my favorites:

He was enormously fat, as if he had passed much of his life in a sphere where human conditions of growth no longer pertained [...]

The hull itself — scarred and scraped, ablated through contact with some indescribable medium, as if wormhole travel meant a thousand years in a coffee-grinder, motion as Newtonian as a ride on a runaway train — cooled quickly down through red to plum-coloured to its normal thuggish grey.

Buffo was tall and thin, with a loose, uncoordinated gait which made him look as if the wrong legs had been attached to him at birth.

Sound In Viriconium

Their fires flared in the twilight, winking as the men moved between them. There was laughter and the unmusical clank of cooking utensils. They had set a watch at the centre of the bridge. Before attempting to cross, Cromis called the lammergeyer to him. Flapping out of the evening, it was a black cruciform silhouette on grey.

Redundancy is a perfectly valid component of fresh writing. To understand why, think about how we read. Expected words receive the briefest attention from our minds; two and three word phrases can fuse together into clichés that are nearly invisible to us. (George Orwell talked about how insidious these can be in his essay “Politics and the English Language”.) But novel bigrams like “unmusical clank” force the brain to decode them. By its lonesome, clank wouldn’t summon up that particular sound. Once you prefix it with unmusical, though — and really all clanking is unmusical, even the cowbell’s — now you can hear the sound.

I think it’s the modification of sounds that makes them come alive. You give the reader a basic clip from their own personal soundbank, and then force them to do processing on it. It’s that processing that makes for good description, which is maybe counterintuitive.

As a case in point, here is a sound that we hear twice in the Viriconium stories. Which do you prefer?

Hornwrack’s knife thumps him squarely in the hollow between collarbone and trapezius with a sound like a chisel in a block of wood

Soon after they had entered it the booth began to agitate itself in a violent and eccentric fashion, lifting its skirts and tottering from side to side as if it was trying to remember how to walk—while out of it came a steady rhythmical thumping sound, like two or three axes hitting a wet log.

That adjective, wet, clarifies the sound just that extra bit.

Here are a few more examples of forced processing. The simplest is onomatopoeia:

If a bird called, tak tak, like an echo in a stony gully, the madwoman followed it with her eyes, tilting her head, smiled.

Then we have your basic adjective modification:

The high, naked shriek of a fish eagle echoed over the fells, but there was no moon yet in the sky.

At night the dull ring of his hammer penetrated the intervening walls; he was rearming his little force.

And then there are similes of sound:

The crystal launches clashed with a sound like immense bells.

A cool wind sprang down from Rossett Gill to rustle like a small animal in the bracken.

The typical modifier for a sound in Viriconium is thin. Everything is run-down and worn out in Viriconium, even the sound waves.

On a table he had a machine in a box. When he did something to it with his hands it produced a thin complaining music like the sound of a clarinet in the distance on a windy night, to which he tapped his feet and nodded his big head energetically, while he grinned round the room.

Sheep were bleating distantly as the shepherds drove them down from the upland turf to winter pasture in the valley.

At night the servants heard her singing in a thin whining voice, in some language none of them knew, as she sat among the ancient sculptures and broken machines that are the city’s heritage.

All at once he went and stood in the middle of the room on one leg, from which position he grinned at her insolently and began to sing in a thin musical treble like a boy at a feast:

I could hear the thin voices of the children carrying the tune, blown up the hill with the mist and the rain:

Birkin Grif laughed uncomfortably; a few thin echoes came from his men.

The valley winked out below him; the cliff lurched and spun; he shuddered, and heard a thin piping noise coming out of his own mouth—

Handling Time

Let’s take a look at a passage and focus on how Harrison manages time. As you read, pay particular attention to the verbs and prepositions.

Inside the mist was a distinct smell of lemons, and of rotting pears—a moist and chemical odour which sought out and attacked the sensitive membranes of the body. The light was sourceless, and had the effect of sharpening outlines while blurring the detail contained within them: on Hornwrack’s right, the dwarf looked as if he had been cut from grey paper a moment before—a tall queer hat, a goblin’s profile, an axe head bigger than his own. Beyond this paper silhouette the path fell away into a whitish void in which Hornwrack made out now and then a localized and fitful carmine glow.

To be, the most common verb in any narrative, is a verb of stasis. In fact, among the verbs it’s kind of a black sheep, since existence is a pretty weak form of action. But it is of course so useful to be able to tell a story with better-than-slow-motion technology. You can capture six different impressions and run through a whole inner monologue at the speed of thought. At the same time, no reader wants to stand tapping their foot while you gleefully exercise this power. Harrison never spends more than a couple sentences lingering between active verbs. Here we get a quick sniff and glance at our surroundings.

While he was trying to remember what this reminded him of, Alstath Fulthor took station on his left. Their throats raw, their eyes streaming, and their noses running, they advanced in a cautious formation until the path began to level out and they found themselves without warning on a wide stone concourse bordering the estuary.

That initial while gets the tape running again, and that until fast forwards us to the next moment of interest.

Here the mist was infused with a thin yellow light. But for the slap of the waves on the water stair below, but for the silence and the smell of the fog, they might have been in the Low City on any cold October night. Hornwrack led them to the water’s edge, the hooves of the horses clacking and scraping nervously across an acre of worn stone slabs glistening with shallow puddles. A languor of curiosity came over them. Despite their forebodings they tilted their heads to hear the distant thud of wood on wood, the faint cries of men echoing off the estuary. Even Fay Glass was quite silent.

Something that always confused me: the convention of using here and now in past tense narrative. In any case, Harrison displays his usual concern for light, charting its fluctuations as the group wanders through the mist.

Hornwrack narrowed his eyes. “Fulthor, there are no longer fishermen in this place.” Distances were impossible of judgment. He wiped his eyes, coughed. “Something is on fire out there.”

The smell of smoke had thickened perceptibly, perhaps carried to them by some inshore wind. With it came a creaking of ropes and a smell of the deep sea; groans and shouts startlingly close.

This move right here, the “had thickened perceptibly,” is why I chose this passage. It’s a retroactive description, unacknowledged until needed, at which point the reader integrates it.

More than anything, what I look at as I’m studying writers is how they fold together their sentences. If you are describing a consecutive sequence of actions, there is nothing to it: you just rattle off SVOs (Subject Verb Objects) until that sequence completes. But once you begin jumping around time and/or space, a little more syntactical work must be done to ensure the reader makes the jump too. As we’ll see presently, Harrison leads off with a now to inaugurate a new sequence.

Now a node of carmine light appeared, expanding rapidly. A cold movement of the air set the mist bellying like a curtain. Hornwrack shook his head desperately, looking about him in panic: abruptly he sensed an enormous object moving very close to him. The mist had all along distorted his perspectives.

“Back!” he shouted. “Fulthor, get them back from the water!” Even as he spoke the mist writhed and broke apart. Out of it thrust the foreparts and figurehead of a great burning ship.

There’s a paragraph break here, after which some description feels natural and appropriate. (Strange how something as under the radar as an indent can prime you for a downshift in pace.) At this point I don’t have much to say about the treatment of time, but I want to include this last paragraph because it’s fun.

Its decks were deep with blood. Once it had been white. Now it rushed to destruction on the water stair, spouting cinders. Its strange slatted metal sails, decorated with unfamiliar symbols, were melting as they fell. Captained by despair, it emerged from the mist like a vessel from Hell, its figurehead an insect-headed woman who had pierced her own belly with a sword (her mouth, if it could be called a mouth, gaped in pain or ecstasy). “Back!” cried Galen Hornwrack, tugging at his horse’s head. “Back!” Fay Glass, though, only stared and sneezed like an animal, transfixed by the mad carven head gaping above her. Dying men tumbled over the sides of the ship, groaning “Back!” as the lean, charred hull drove blindly at the shore; “Back!” as it smashed into the water stair and with its bow torn open immediately began to sink.

Riding high off the truly metal sentence I bolded, Harrison makes the unusual move of interspersing the narration with Hornwrack’s desperate commands.

Block Characterization

I got the term “block characterization” from a narratologist named Manfred Jahn, specifically from this page. The term refers to those one or two paragraphs of description that frequently attend a character’s introduction to the narrative.

It’s a fundamental skill for authors, and we need to master it like a chef needs to master reductions. (Same concept, by the way — how to reduce a person to a paragraph?)

tegeus-Cromis

Cromis was a tall man, thin and cadaverous. He had slept little lately, and his green eyes were tired in the dark sunken hollows above his high, prominent cheekbones.

He wore a dark green velvet cloak, spun about him like a cocoon against the wind; a tabard of antique leather set with iridium studs over a white kid shirt; tight mazarine velvet trousers and high, soft boots of pale blue suede. Beneath the heavy cloak, his slim and deceptively delicate hands were curled into fists, weighted, as was the custom of the time, with heavy rings of nonprecious metals intagliated with involved cyphers and sphenograms. The right fist rested on the pommel of his plain long sword, which, contrary to the fashion of the time, had no name. Cromis, whose lips were thin and bloodless, was more possessed by the essential qualities of things than by their names; concerned with the reality of Reality, rather than with the names men gave it.

He worried more, for instance, about the beauty of the city that had fallen during the night than he did that it was Viriconium, the Pastel City. He loved it more for its avenues paved in pale blue and for its alleys that were not paved at all than he did for what its citizens chose to call it, which was often Viricon the Old and The Place Where the Roads Meet.

He had found no rest in music, which he loved, and now he found none on the pink sand.

Alstath Fulthor

Fulthor, that myth!

He was the enigma of the Low City, the meat and drink of their gossip. In the streets beneath Minnet-Saba all motion ceased at his comings and goings, whatever the hour. The constant bedlam of the gutters abated as he rode by, wrapped in his queer diplomatic status and his queerer armour with its strangely elongated joints at knee and elbow and its tremulous blood-red glow. Who was he? Did he serve the city, or it him? He was like some living flaw in time, through which leaked faint poisonous memories of the Afternoon—its fantastic conspiracies and motiveless sciences, all its frigid cruelties and raging glory. Since his triumphant entry at the head of the Reborn Armies eighty years ago (the Northern wolves driven before him to be caught at last between his hammer and the anvil of Tomb the Giant Dwarf), he had gone about Viriconium like the courier of a god, the very beat of his heart a response to some lost prehistoric cue. He was a miasmal past and an ambivalent future, a foreign prince in a familiar city. He was, and always had been, the repository of more fears than hopes.

The sentences in this description are so frenetic because it is from A Storm of Wings, which came nearly a decade after The Pastel City, during which time Harrison distilled the bombastic techniques he experimented with in TPC to their maximum potency. Which is why there is an adjective in the pot of every noun and a simile in every sentence’s garage.

As we review these descriptions, you’ll notice that only a few variables are hit upon. These are the degrees of freedom that can fix a character. They are:

- Physical characteristics (face, physicality, dress)

- Habits

- Position within society (how others see them)

- Self-image

- Biography

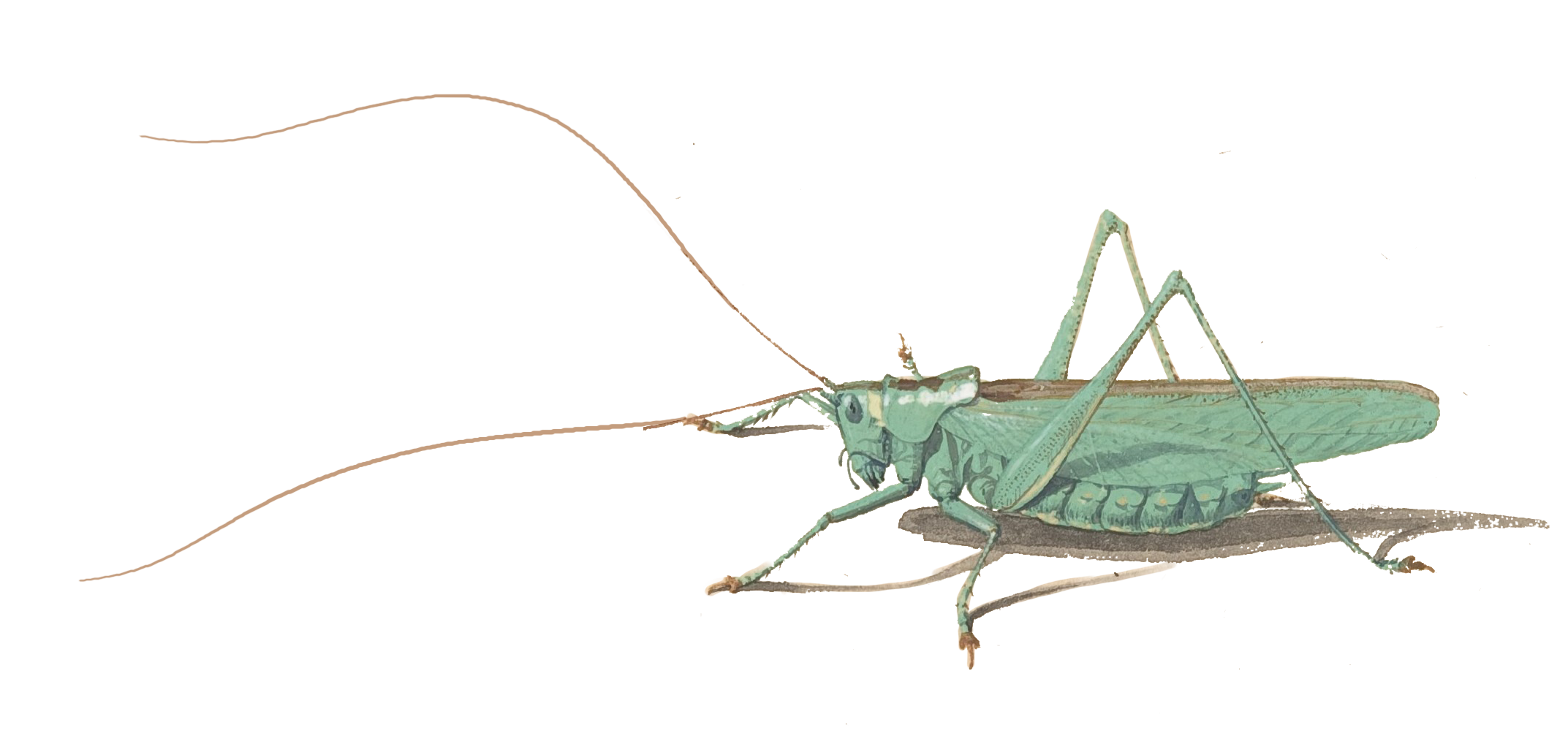

Elmo Buffin

Elmo Buffin, that sad travesty, with his limbs like peeled sticks! He was seven feet tall and a yellow cloak was draped eccentrically about his bony shoulders. Plate armour of a dull-green colour encased him, sprouting all manner of blunt horns and spurs, little nubs and bosses which seemed chitinous and organic. It pulsed and shivered in its colour, for it had come to him from his father, a Reborn Man of the defunct House of medina-Clane, one of the first to be resurrected by Tomb the Dwarf and now dead. What his mother—a dour Northwoman and fishwife of Iron Chine, whose first husband had died in the War of the Two Queens—had bequeathed him is hard to say. Neither strain had bred true, for between Afternoon and Evening there is a great genetic as well as temporal gulf. Epilepsy racked him twice a week. His eyes were yellow and queer in that slack clownish face, which seemed too large for his thin limbs. His brain heaved like the sea; across it visions came and went like the painted sails of his own fleet. Of years he had twenty-six; but his insanity made of that forty or fifty. Since the death of his father (himself an eccentric but principled man, who had consented to the miscegenation in order to cement the two halves of his biracial community) the whole weight of the Chine had rested on his shoulders.

"The clothes make the man," as they say, so he start with Buffin’s armor and starts digging.

Buffin is one of the more interesting characters in A Storm of Wings, I think because of this dense family history and the great sentence about how insanity can stretch 26 years into 40 or 50.

Emmet Buffo

Buffo was tall and thin, with a loose, uncoordinated gait which made him look as if the wrong legs had been attached to him at birth. His face was clumsy and long-jawed, he had limp fair hair and a pale complexion. Years of staring through homemade lenses had given his eyes a sore and vulnerable look. His researches, which had something to do with the moon, were regarded with derision in the High City. He did not suspect this. Lately, though, he had been short of funds. It had made him absentminded; when he thought no one was watching him his face became slack and empty of expression.

Buffo emerges from the impressive list of descriptors attributed to him in just three sentences:

Tall, thin, loose, uncoordinated, wrong, clumsy, long-jawed, limp, fair, pale, sore, vulnerable.

In other words, the sad clown, much like his predecessor Elmo Buffin. What makes him sadder still is that bit about the High City’s derision towards his research, a derision he is unaware of. As we’ll see in a moment with the Grand Cairo, a lot can be gotten out of the delta between a character’s self-image and the narrator’s image of him.

Ansel Verdigris

The poet was a rag of a man, little, and hollow-cheeked from a life of squalor, with his bright red hair stuck up on his head like a wattle and greed lurking in the corners of his grin. He gave his small hands no rest— when he was not trying to palm cards or filch the bottle, he was flapping them about like a wooden puppet’s. At slow moments during the play he would stare silently into the air with his face empty and his mouth slack, then, catching himself, leap up from the three-legged stool on which he sat and go jigging round the booth until by laughing and extemporizing he had got his humour back. In mirth, or delivering doggerel, his voice had a penetrating hysterical timbre, like a knife scraped desperately on a plate. He had made a “ballade of stewed cabbage” earlier that evening, but seemed to hate and fear the smell of the stuff, grimacing with dilated nostrils and turned-down mouth when a wave of it passed through the booth. His name was Ansel Verdigris, and the fat woman across the card table was his last resort.

I am outraged by the description of Ansel’s hair as a wattle. The wattle is a bit of flesh hanging down from neck of a bird. The coxcomb is a bit of flesh jutting up from the pate of a bird. Same thing, only one makes way more sense as a descriptor for hair! And I know this to be true because a character in the next novella, Ashlyme the painter, is consistently described as having a coxcomb of hair!

Chicken anatomy aside, I like this block characterization because it’s somewhat unusual. The description of Elmo Buffin, above, is more typical: the physicality of a character and something of his past. In contrast, Ansel’s portrait is drawn through activity, indicating his rambunctiousness.

Ashlyme the portrait painter

He was a strange little man to have got the sort of reputation he had. At first sight his clients, who often described themselves later as victims, thought little of him. His wedge-shaped head was topped by a coxcomb of red hair which gave him a permanently shocked expression. His face accentuated this, being pale and bland of feature, except the eyes, which were very large and wide. He wore the ordinary clothes of the time, and one steel ring he had been told was valuable. He had few close friends in the city. He came from a family of rural landlords somewhere in the midlands; no one knew them. (This accident of birth had left him a small income, and entitled him to wear a sword, although he never bothered. He had one somewhere in a cupboard.)

If you compare this to the tegeus-Cromis description, you’ll see how much less stress there is on any one of these sentences. They begin with a he or a his and simply lay out of the facts of Ashlyme’s life. He looks like this, he wears these clothes, he comes from here. It’s the sword in the cupboard that brings Ashlyme together for me; it says so much about how he relates to his class status.

I’m currently gathering up the character descriptions in George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire, and there is a ridiculous emphasis there on eye color. It’s like Martin is taking a police report, noting the eye color along with height, weight, hair color, and any distinguishing marks and scars. Harrison talks about eyes as well, but focuses on how they sit in the face. Ashlyme is shocked-looking, Emmett has sore and vulnerable eyes.

The Grand Cairo

The Grand Cairo was a very small man of indeterminate age, thick-necked, grown fattish in the middle. “I like to think of myself as a fighter,” he was always saying, “and a veteran of strange wars.” He did move with a light, aggressive tread, much like that of a professional brawler from the Plaza of Unrealised Time, and sometimes quite disconcerting: but he had too sly a glance even for a common soldier; and drinking bessen genever, a thick black-currant gin very popular in the Low City, had ruined his teeth, lent his eyes a watery, spiteful cast, and made his forearms flabby. Nevertheless he had a high opinion of himself. He was proud of his hands, in particular their big square fingers; showed off at every opportunity the knotted thigh muscles of his little legs; and kept his remaining hair well oiled down with a substance called “Altaean Balm,” which one of his servants bought for him at a stall in the Tinmarket.

Ashlyme found him waiting impatiently by a window. He had on a jerkin with heavily padded shoulders, done in gorgeous dull red leathers, and he had arranged himself in the curious hollow-backed pose—hands clasped behind his back—he believed would accentuate the dignity of his chest.

The Dwarf is one of the recurring character archetypes in Viriconium. Tomb the Iron Dwarf is the hardass, Rotgob the jester, and the Cairo the egomaniac. Harrison quotes the Cairo on the Cairo, which is a technique to consider. We can learn a great deal by seeing how a character self-describes. The Cairo is clearly impressed with himself, but that “he believed” in the last sentence lets you know the narrator isn’t buying it.

One other thing you can learn from the Cairo is the value of having a few items associated with a character. Much like George Clooney’s character in O Brother, Where Art Thou?, the Cairo swears by his pomade. So whenever he appears, Harrison can mention its sharp scent. Same with the bessen genever.

Mr. Ambrayses

His laughter seemed to sensitise me to him, and I began to see him everywhere, like a new word I had learned: in his garden where the concrete paths, glazed with rain, reflected the sky; in Marie’s café, a middle-aged man in a dirty suede coat, with jam on his fingers—licking at them with short dabbing licks like a child or an animal; in Sainsbury’s food hall with an empty metal basket in the crook of his arm, staring up and down the tinned-meat aisle. He didn’t seem to have anything to do. I saw him on a day-trip bus to Matlock Bath, wearing one sheepskin mitten. His trousers, which were much too large for him, so that the arse of them hung down between his legs in a gloomy flap, were sewn up at the back with bright yellow thread as coarse as string.

Ambrayses is a type, the shabby bachelor. His features do not need description because his clothes tell you everything about him. The suede coat is dirty, he’s managed to lose a mitten, his too-large pants have been clumsily mended.

This is a montage type description, where we glimpse him briefly within a couple of scenes. Usually block descriptions don’t focus on the character within a setting, but the places Ambrayses can be found says a lot about him. He goes down the tinned-meat aisle!

A Typical Passage: The Cinemagraph

Hornwrack and Fulthor confronted in a stony cleft among dwarf birch and oak. A chalky light, slanting down between the brittle boughs onto banks of heather and bilberry, revealed the Reborn Man sitting quietly on an unfinished millstone, his features as white and careworn as those of a praying king. A pied bird absorbed his attention: it hopped from stone to stone, tilting its small bright eye to watch him. Chill airs rattled the twigs above his head, stirred his yellow hair. The baan in his hand flickered like a firework in the hand of a child; he had forgotten it. Votive and calm in his scarlet armour, he looked like the invalid knight in the old painting; and the overhanging towers of the Agdon Roches, with their silent gullies and damp sandy courses, rose up behind him through a screen of black branches like the buttresses of an ancient chapel.

Here, Harrison sieves a description through a dense mesh of allusions to Arthurian legend. The Fisher King is an important motif to the Viriconium stories — I say that so confidently because my lit professor was baffled when I confessed I hadn’t made the connection, so obvious was it to him — and here we have reference to an invalid knight, and, just out of frame of our excerpt, a “wounded king”. Perhaps the “pied bird” is a kingfisher? What about the ancient chapel... maybe the chapel perilous, also referenced in The Waste Land, which Harrison notes as an influence?

Considering the frequent and unearthly apparitions of Benedict Paucemanly, and Harrison’s knowledge of tarot, I would be surprised if this were not on his mind during the writing:

“Chapel Perilous” is also an occult term referring to a psychological state in which an individual cannot be certain whether they have been aided or hindered by some force outside the realm of the natural world, or whether what appeared to be supernatural interference was a product of their own imagination. (per wikipedia)

Leaving aside the allusions, I like this passage simply as a kind of textual cinemagraph. There are the usual earmarks of a Harrisonian description — light and specific vegetation — but also small bits of activity around the calm center of the composition, Alstath Fulthor. See how Fulthor gets no active verbs during this description. He does not look at the pied bird, but rather the pied bird absorbs his attention. The wind rattles the twigs, stirs his hair. Then, amidst the religious imagery and diction, a startling simile:

The baan in his hand flickered like a firework in the hand of a child; he had forgotten it.

One of those great similes, so out of keeping with the rest of the paragraph and improved by that fact.

A Typical Passage: Impertinent Figures

Dawn had hardly warmed the air. Now brittle flakes of snow came down, reluctantly at first and then with more vigour until Cobaltmere was obscured and the marsh around it began to look like the ornamental gardens of Harden Bosch seen through a net curtain in Montrouge. If you concentrated for a moment on the flakes that made up any part of the curtain they would seem to fall slowly, or even to be suspended: then, with the movement of flies in an empty room in summer, whirl round one another in a sudden intricate spiral before they shot apart as if a string connecting them had been cut. In this way they whirled down on the shore of the lake; they whirled down on the face of the dwarf. The prince, huddled in his cloak, touched the turned earth with his foot. He pushed some of it into the hole.

Obnoxious as I sound saying it, this strikes me as “classic early period” Harrison. The figurative language is so energetic it cannot settle on any one comparison: first the small leap to another snowy scene, then the more surprising likeness to flies in a summer room. And then the final thought about the connecting string.

And of course I can’t read about snow without being reminded of “The Dead”, by James Joyce. Harrison’s repetition of “whirled down” evokes Joyce’s repetition of falling.

A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on his journey westward. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

A Typical Passage: Hornwrack The Kamikaze

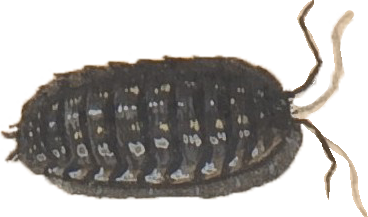

One of my goals in these studies is to discover quintessential passages. This, from the last doomed flight of the pilot Galen Hornwrack, fits the bill. As they say on the talk shows, this is not an easy clip to set up, but here goes: a race of sentient mantids have infested the earth. This scene takes place in their mad city, at the center of which is the tortured, mutated body of a man named Benedict Paucemanly, who flew to the moon a century prior and was captured there by some ancient machinery, and converted into a sort of living satellite dish. In his new, nightmarish position of intergalactic antenna, Benedict drew the attention of these insects. And then... well, I get a little lost here, but the point is he and the insects made it to earth, and poor Benedict is now trapped in a life-support vat, where he serves as a surrogate mother for the insects’ larvae.

Galen Hornwrack, who used to fly airboats, discovers in this insect city the Heavy Star, the very same vessel that took Paucemanly to the moon. In his agony, Paucemanly telepathically begs Hornwrack to put him out of his misery, and here we read as Hornwrack tries to oblige.

Okay, hope that was comprehensible. On with the text. Here are the hallmarks I’d like you to notice. They may only appear once or twice in these paragraphs, but the rest of this study should convince you of their wider prevalence.

- Similes, some quite unusual

- “as if”. Just one here, but it pops up a lot elsewhere.

- some, as in “the movements of some tiny damaged mechanical toy.” Another way to work in similes, shows up all over the wider text.

- Rare words, perfectly selected. (Google Image search bolide, please)

- An active, animated narrator. (Exclamation points, siding with the audience with a “we can see”)

- noun modifiers. (“tub-like head”, “cruel calm”, “fatal faltering”, “cabbagey air”)

- The indescribable and ambiguous. (“Unimaginable journeys,” the mysterious listlessness that condemns Hornwrack.)

- “Energetic” adverbs, usually succeeding the verbs they modify. (I put energetic in scare quotes because that’s a subjective judgment. But wriggles ecstatically and bursts pulpily just sound vibrant to me.)

- Painterly attention to light and visual effects. (Persistence of vision, “violet strokes on an obsidian ground”)

They fastened themselves on to its outer hull like locusts on a branch. It strained forward as if the air had solidified around it, and was brought to a standstill above the perimeter of the city, where the hulk of Benedict Paucemanly greeted it with booms and roars of self-pity, waving his infested limbs. (From up on the watershed this activity seemed like the movements of some tiny damaged mechanical toy.) He had replaced his mask but was unable to secure it, so that it hung awry on his blubbering tub-like head like the woollen cap on the head of a retarded child. His new organs pulsed, engorging themselves in time to the rhythms of the city. “In the moon,” he said, “it was like white gardens.” He begged for freedom in an abandoned language. He blinked up, watching the insects as they continued to alight on his old ship. When they could find no further space to settle, they attached themselves to one another in a parody of copulation. Beneath this rustling layer the Heavy Star struggled to gain height. Suddenly, violet bolides arced from its bows! Caught up in the discharge of the ancient cannon, many of the insects dropped away, crackling and roasting and setting fire to their neighbours, so that they fell about the ears of the decaying airboatman like burning leaves.

Fear death from the air! Up there, we can see, Hornwrack fears nothing. He makes the boat his own. Power plants enfeebled by its unimaginable journeys, substructure creaking like an old door, it nevertheless wriggles ecstatically under his hands, light flaring off its stern. We see it even now, long after the fact, rolling and spinning against the southern quadrant of the sky. The patterns it is making are gay, adventive, dangerous. It tumbles off the top of a loop and falls like a stone. It soars eighteen hundred feet vertically upwards, spraying violet fire almost at random into the dark green varnished sky. Persistence of vision makes of it a paintbrush, violet strokes on an obsidian ground, while the insects fall like comets all around it, trailing a foul black smoke, to shatter and burst pulpily on the plain beneath! Even the watchers on the watershed have abandoned their cruel calm. He may yet escape! something whispers inside them. He might yet escape! . . . But now the energy cannon has stopped working, and he seems to have undergone a fatal faltering or change of heart. They bite their lips and urge him on. Some listlessness, though, prevents him: something inhaled from the cabbagey air of the Low City long ago. Now the Heavy Star drifts immediately above Paucemanly’s carcass like an exhausted pilot fish. The insects descend. All Hornwrack’s efforts have made no impression on their numbers. One by one they approach the wallowing vehicle. One by one they settle on its creaking, riven old hull and commence to bear it down....

A Typical Passage: The One That Got Me Started

I became a writer by a simple process that took twelve years to complete. In 3rd grade I wrote a story and read it to my class, which liked it. That was my early taste of success. In senior year of high school a teacher challenged me to try National Novel Writing Month, and I finished it despite a late start (November 9th). That convinced me I could do the job. As a college sophomore I took a workshop with Steve Stern, my first encounter with a living breathing author, and I thought — yeah, I could see myself doing this.

But in between the NaNoWriMo and that writing workshop, I had not yet decided on being a writer. Though I was fooling around with some text documents, I still thought of myself as a reader. Still, my reading habits had changed. The experience of writing a short novel had made prose technique visible to me, and I started to notice how the professionals handled problems with their sentences. I developed strong opinions about what a good sentence sounded like. I began to draw stars in the margins of my books, give the stink-face to paragraphs. Particularly good ones were now lodging in my memory. This was the first:

The room was cold. Audsley King lay on the sofa — thin, still, dazed-looking — wrapped in a fur coat with curiously huge sleeves. She spoke reluctantly of “thieves”; her eyes moved apprehensively every time a builder’s cart went past the house. Bowls of anemones stood on every flat surface, as if she had begun to mourn herself. The flowers were purple and wine red, the colours of her disease; their necks were bent compliantly.

I have perfect recall of the moment I read that passage: it was a damp October, freshman year, I was sitting up in bed with a pillow at the small of my back and a desk lamp shining over my shoulder. There was something about that phrase, “purple and wine red, the colours of her disease.” It may have been the pure literariness of the observation, maybe it was just the British spelling of colors. Whatever its appeal, it was obviously a deep one. These sentences were the first of many that started me down a road which I’ve followed — for eight years and 1.5 million words — back to here. I can’t analyze this! I’m too sentimental!

Okay fine I’ll do it.

That five-sentence paragraph encapsulates many of Harrison’s virtues post-70s. You get the impression of tight control from the staccato rhythm — created by the colons, semicolons, and em dashes — and the simple observations so confidently deployed: “the room was cold”, “bowls of anemones stood on every flat surface”. The potential frostiness of this approach is warmed by modifiers. Some are unremarkable — reluctantly, apprehensively — and others give a hitch: at what point are sleeves curiously huge? My feeling when I read Harrison is that I am inhabiting an animated universe, one pulsing with meaning. Whatever the narrator’s attention focuses on, living or dead, it answers, helps tell the story. The flowers reflect Audsley King’s illness, they bow their heads out of respect for the dying woman.

That effect comes from Katherine Mansfield. Harrison, in the Strange Horizons interview:

She had gone underground and you were hearing her voice speaking from every part of the fiction, even the furniture in the central character’s front room.

The Influence Of Katherine Mansfield

There’s a great interview with Harrison in Strange Horizons that I recommend you read in its entirety.

CM: Every time I hear you talk about your writing you make reference to your admiration for Katherine Mansfield. What impresses you most about her work?

MJH: Oh God, what doesn’t? Mansfield went all the way underground in the text. She called it “muted direction.” She wouldn’t say, “Look here, this is the evil character; look here, this is the good character; look here at what the evil character does to the good character, isn’t that so evil? And look how good the good character has been about it!” Katherine just seemed to show you people doing their stuff. If, as the reader, you drew moral conclusions about them, if you drew conclusions of any sort, they were yours. Of course she was cheating. She wasn’t absent from the text. She had gone underground and you were hearing her voice speaking from every part of the fiction, even the furniture in the central character’s front room. Of course, she got pilloried for being “amoral” and “cold.” That was to miss the point — the reason you were horrified was she had done her work right!

When I first bumped into her stuff in the late ’70s I was gobsmacked. As a result, there’s no comparison between A Storm of Wings and The Ice Monkey. That’s the pivot point. They aren’t even in the same county, those two. In Viriconium works a bit better. It’s lighter, freer; it skates across its own surface to make itself.

In Viriconium is my favorite of the Viriconium stories, perhaps my favorite thing Harrison has written. I’d like to identify how Harrison’s technique differs there in comparison to the earlier novels.

Compared to his contemporary work, Harrison performs much closer to the edge of the stage in the Viriconium cycle. By that I mean you are much more aware of the writer’s presence. That awareness can come from the use of a “we” or an “our”, as in a phrase like “as we shall soon see,” or from eye-catching figurative language like this:

But a blade nicked his collarbone, and death demanded his attention. He gave it fully. (from The Pastel City)

Nowadays, Harrison is much more behind the scenes, giving just as much information but in such a way that the narrator never separates from the narration; the effect is of an animate narration which tells itself without the assistance of a human, like a player piano.

There are some obvious changes in tone and content. The Pastel City and A Storm of Wings are much closer to the epic fantasy, while In Viriconium is a literary chamber play. That means the sentences are much different. In contrast to the slightly try-hard sentences of TPC, the sentences in IV are relaxed, simple unless they have a good reason not to be. To see how this works in practice, compare the characterizations of tegeus-Cromis and Ashlyme the painter. When I read that Cromis description, which is the introduction of The Pastel City, I feel like the sentences are a size too small for the information within them, and I’m a little put off by the highly parallel structures and cutesy reversals. (In one sentence we learn Cromis wears rings “as was the custom of the time” but does not name his sword, “contrary to the fashion of the time”.)

This full-to-bursting style quickly becomes really potent, however, and Harrison is absolutely swashbuckling with it by the time he writes A Storm of Wings, nine years later. Still, like all displays of virtuosity, it can become overwhelming. IV appears to be doing so much less on the level of the sentence, but you soon begin to appreciate the confidence of its minimalism.

But the prose style is not what elevates IV over the earlier stories: that would be the narrator’s relationship to the reader. Inspired by Mansfield as we read above, it is a complex, indirect style, and in fact there is a lot of free indirect in it. (Per Wikipedia, “Free indirect speech is a style of third-person narration which uses some of the characteristics of third-person along with the essence of first-person direct speech.”)

In practice it looks like this.

The haemorrhage had left her disoriented but demanding, like a child waking up in the middle of a long journey. She forgot his name, or pretended to. But she would not let him leave: she would not hear of it. He would set up his easel like a proper painter and work on the portrait. Meanwhile she would entertain him with anecdotes, and the Fat Mam would read his fortune in the cards. They would make him tea or chocolate, whichever he preferred.

Ashlyme, though, had never seen her so pale. Should she not go to bed? She would not go to bed. She would have her portrait painted. In the face of such determination, what could he do but admire her harsh, mannish profile and white cheeks, and comply?

There are no quotation marks in there but you can hear snippets of dialogue anyway, mixing freely with the usual narration.

We can see more of this when Ashlyme is accosted by the quarantine police when he tries to visit Audsley King.

They were polite, since he had obviously come down from the High City, but firm. They took his easel from him so that he would not have to be bothered carrying it. They led him back up the steps and into a part of the city which lay behind the fashionable town houses and squares of Mynned, where the woody parks and little lakes, the summery walks and shrubberies of the Haadenbosk merged imperceptibly with that old and slightly sinister quarter which had once been known as Montrouge. Here, they said, he would have a chance to explain himself.

It is an exciting style of writing. Instead of the text being the exclusive channel by which the narrator sends his communiqués — along with the occasional interruption from the dialogue channel, in which all operators must conclude every transmission with their call sign — it’s sort of an open frequency, in which broadcasts overlap and compete with one another. In this paragraph, we hear the police make their chummy threats:

They were polite, since he had obviously come down from the High City, but firm.

That "obviously" sounds like cop talk. “I can see you’re busy sir, I won’t take but a moment of your time...”

But who names them polite? That could be Ashlyme or the narrator, it’s hard to tell. Whoever it is, you’ve got two subjectivities braiding together in one sentence. (And by the way, this is a supremely efficient way to write, because you can tuck whole dialogue exchanges into a single clause.)

Another example:

They took his easel from him so that he would not have to be bothered carrying it.

Again we hear the Big Bad Wolf routine. Is Ashlyme encumbered by his easel? Of course not. All the best coercion has some innocent interpretation, no matter how tenuous, so that the put-upon party can be dismissed as overly dramatic if he says what is really going on.

“You’re trying to intimidate me!”

“Nonsense, my dear man, we’re simply trying to relieve you of your burden.”

Since the text presents all of this without comment, it is ostensibly allowing the police’s bullying to go unchallenged. It gives us no nod to say, “we both know what these fellows are up to, don’t we?” This is the “muted direction” that Harrison (and Mansfield originally) is talking about.

A more direct and less interesting way to handle this might go something like,

One of the policemen took his easel. “There, now you won’t have to be bothered with carrying it,” he said, with a nasty smirk.

Here the different voices are more clearly delineated and some authorial judgment is rendered with that “nasty smirk.”

Harrison doesn’t do that because he trusts the reader to decode this (and we will, automatically). Such prose, heavy on implication, is satisfying to read because you get to flex your interpretive muscles a bit. And there’s an added bonus. With the narrator’s temporary disappearance, we’re not protected from the text. We are being menaced by these policemen just like Ashlyme, and so we empathize more strongly with him.

Narration like this is somewhat coy, or perverse. It messes with the reader, makes you pay attention. Sometimes the narrator of IV will play dumb.

“Look,” he said. “That’s the fishmonger following us. I saw him in the High City this morning, and he had some nice hake. I think I’ll cook a bit of that for tea.” He was unlucky. For some reason, as soon as he saw Buffo approaching, the fishmonger went into a side alley and made off, his barrow clattering on the cobbles.

Clearly Buffo and Ashlyme are being pursued by the secret police. But the narrator presents this moment as it appears to the somewhat dim Buffo. (Buffone is Italian for clown, and buffo means funny.)

We have to relate to such a narrator differently. It’s like dealing with an oracle: they’ll give you in the information, but nobody said they had to be straightforward about it.

Harrison says in his Strange Horizons interview:

To go back to Katherine Mansfield: if you just present the events to the reader (or appear to), then the complexity of human motive will spin off that. If you try too hard to determine the way the reader sees character and motivation, you will actually restrict the reader’s interpretive opportunities. By limiting the amount of guidance you give, you automatically get the depth and complexity of interpretation you want. Because that’s what we readers do in real life — we interpret people’s actions and thus assign them “motive” and “character.”

Whenever you read a story with an artist in it, you can bet some statement is being made about the practice of writing itself. How could it be otherwise? The protagonist in In Viriconium is a painter named Ashlyme, and I think he’s a way for Harrison to process the reaction Mansfield received, which he mentioned in that Strange Horizons interview: “Of course, she got pilloried for being ‘amoral’ and ‘cold.’”

Ashlyme gets the same treatment.

Ashlyme the portrait painter, of whom it had once been said that he “first put his sitter’s soul in the killing bottle, then pinned it out on the canvas for everyone to look at like a broken moth,” kept a diary.

He is popular with bourgeois women, but they change their tune once he draws their portrait:

He always lost two or three of these clients when the finished portrait turned out a little less “sympathetic” than they had expected

Which leads him to write in his diary:

“La Petroleuse” complains that I have made her look provincial. I have not. I have given her the face of a grocer, which is another matter entirely, and in no way a judgment.

Here we have an artist rejecting the obligation to create sympathetic characters. For Ashlyme, his sitter is missing the point. Producing a sympathetic rendition of a person is not even how he conceives of his task, the term is so meaningless to him that it merits scare quotes.

What counts, then? What advantages are gained by embracing the killing bottle? By discarding moralistic judgments and more fully embracing an objective view of all the characters, the narrator (and reader) can more easily dart into the subjectivities of these characters — empathy requires a suspension of judgment. But by being such a free agent, the narrator necessarily comes off as ironic: though his performance of each subjectivity is in earnest, there are so many of these performances and they are cycled through so quickly. Taken together, all this adds up to the very best sort of narrator that modernism can give us: disinterested, sharp-eyed, but not unkind.

The question then becomes: what motivates such a narrator? Why write about such disappointing subjects?

Idealism, I think.

The Marchioness blinked into her teacup. It seemed for a moment she would not answer. Finally she said: “You judge people by unrealistic standards, Master Ashlyme. That is why your portraits are so cruel.” She looked thoughtfully at the tea leaves, then got to her feet and took the arm of her novelist. “Though I daresay we are as stupid as you make us appear.”

Harrison, in Strange Horizons:

Despite rumors to the contrary, I’m a romantic and an idealist. What I write seems bleak, but it stems from my understanding of what people are: this raw, raging, aching bundle of desire. Of course we have to learn to handle that, both as writers and people.

Recyling Your Own Material

Harrison frequently recycles his own material, and as a frequent reader of his, let me say that I enjoy the effect: seeing the same image repeat in text after text imparts a certain charge to it. It’s interesting to see the same piece in different contexts — where does it work best? Perhaps Harrison is slotting these in, again and again, until they finally fit right, and are retired.

Here’s one that seems to haunt him, since it’s showed up over a span of four decades.

... the madwoman, wrapped from head to foot in a thick whitish garment and turning aimlessly this way and that like something hanging from a privet branch. (A Storm of Wings)

All he saw was a sad reticulated greyness, and, suspended indistinctly against it in the distance, something like a chrysalis or cocoon, spinning at the end of its thread. (A Storm of Wings)

“He is dead,” said Hornwrack, who now discerned a sad grey ground, and against that something spinning at the end of a thread. “What’s happened here?” (A Storm of Wings)

Without warning, Audsley King—dreaming perhaps—drew her knees up to her chin, and the sheet contracted like a ghostly chrysalis in the gloom. (In Viriconium)

She was looking out of the window into the narrow passage where, dearly illuminated by the fluorescent tube in the kitchen, something big and white hung in the air, turning to and fro like a chrysalis in a privet hedge. (Course of the Heart)

The first thing Kearney saw outside Meadows’s workspace was the shadow of the Shrander, projected somehow from inside the building onto one of these. It was life-size, a little blurred and diffuse at first, then hardening and sharpening and turning slowly on its own axis like a chrysalis hanging in a hedge. (Light)

It was a difficult morning. Though he tried to persuade her, she wouldn’t eat anything. Before they could leave, the child was back, wrapped tightly in its shawl, spinning this way then that below the ceiling like a chrysalis in a hedge. (Nova Swing)

No doubt it’s a good one. There’s an oblique horror to a chrysalis, the sinister twisting motion as something arranges itself within. (I learned recently that, while pupating, caterpillars liquefy themselves into a pluripotent stew.)

An image that repeats seven times is hard to miss. But even three times is enough, provided the image is striking enough:

Their grinning faces bobbed over Ashlyme in the twilight like red balloons

A face stalked him between the twilit stacks of the ancestral library, bobbing like a balloon.

He had become a specter of himself. His miserable, aggressive face bobbed about above the bed, a tethered white balloon, what flesh remained to it clinging like lumps of yellow Plasticine at cheekbone and jaw, the temples sunken, the whites of the eyes mucous and protuberant.

Sometimes it’s just a phrase...

“The Lamia & Lord Cromis”

He arrived at Duirinish—then a thriving fish-and-wool town on the coast a hundred miles north of the city—towards the end of December, and after making enquiries at a secondhand bookshop and a taxidermist’s, went in the evening to the Blue Metal Discovery, where he sat down in the long smoky parlour at a table some way from the fire.

“A Young Man’s Journey to Viriconium”:

I went to York anyway, and he came with me for some reason of his own—he paid visits to a secondhand bookshop and a taxidermist’s.

... and other times it is a whole paragraph. From Climbers, 1989:

If you untie an old knot, Bob Almanac showed me, the original colours of the rope shine out again from a nest of convolutions — pink, yellow, green, orange, much as they were in a quiet shop on a wet afternoon in winter. “You release the light that was caught up in the knot,” he said. “I think of it as releasing the light.” He smiled shyly. “I thought you’d like that.” Out running in the early morning to avoid the heat, I found three pairs of women’s shoes someone had thrown into a ditch at the top of Acres Lane where it bent right to join the Manchester Road. Delicate and open-toed, with very high heels that gave them a radical, racy profile, they were all size four: one pair in black suede, an evening shoe with a brown fur piece at the toe; one in transparent plastic bound at the edges with metallic blue leather; and a pair of light tan leather sandals with a criss-cross arrangement of straps for the upper part of the foot. Inside them in gold lettering was the brand name “Marquise”. It was a little worn and faded, but otherwise they seemed well-kept. They were still there when I went back the next day, but by the one after that they had gone. I couldn’t imagine who would have thrown them there; or, equally, who would pick them up from a dry ditch full of farmer’s rubbish at the edge of the moor.

“A Young Man’s Journey to Viriconium” (1986?):

He had used up an entire pack of Polaroid film, he told me, photographing three pairs of women’s shoes someone had thrown into a ditch at the top of Acres Lane where it bends right to join the Manchester Road. “I noticed them on Sunday. They were still there when I went back, but by this morning they had gone. Can you imagine,” he asked me, “who would leave them there? Or why?” I couldn’t. “Or, equally, who would come to collect them from a dry ditch among farm rubbish at the edge of the moor?” The pictures, which had that odd greenish cast Polaroids sometimes develop a day or two after they have been exposed, showed them to be flimsy and open-toed: one pair in black suede, an evening shoe with a brown fur piece; one made of transparent plastic bound at the edges in a kind of metallic blue leather; and a pair of light tan sandals with a crisscross arrangement of straps to hold the upper part of the foot.

“They were all size four,” said Mr. Ambrayses. “The brand name inside them was Marquise: it was a little worn and faded but otherwise they seemed well-kept.”

Last one:

“The Incalling”, 1978:

Five or six bellpushes were tacked up by the outer door. I worked them in turn but no one answered. A few withered geraniums rustled uneasily in a second floor window box. I pushed the door and it opened. In some places we’re all ghosts. I swam aimlessly about in the heat of the hall, knocking and getting no response. Up on the first floor landing a woman stood in a patch of yellow light and folded her arms to watch me pass; in the room behind her was a television, and a child calling out in thin excitement.

Clerk lived right at the top of the stairs where the heat was thickest, in three unconnected rooms. I tapped experimentally on each open door in turn. ’Clerk?’ Empty jam jars glimmered from the kitchen shelves, the wallpaper bulged sadly in the corner above the sink, and on the table was a note saying, ’Milk, bread, cat food, bacon,’ the last two items heavily underlined and the writing not Clerk’s. A lavatory flushed distantly as I went into what seemed to be his study, where everything had an untouched, dusty look. ’Clerk?’ Bills and letters were strewn over the cracked pink linoleum, a pathetic and personal detritus of final demands which I tried furiously to ignore; it was too intimate a perspective - all along he had forced me to see too much of himself, he had protected himself in no way. ’Clerk!’ I called. From his desk - if he ever sat at it - he had a view of the walled garden far below, choked like an ancient pool with elder and Colutea arborescens and filling up steadily with the coming night. It was very quiet.

From In Viriconium, 1982:

Audsley King had a confusing suite of rooms on an upper floor. The stairs smelt faintly of geraniums and dried orange flowers. Ashlyme stood uncertainly on the landing with a cat sniffing round his feet. “Hello?” he called. He never knew what to expect from her. Once she had sprung out on him from a closet, laughing helplessly. He could hear low voices coming from one of the rooms but he couldn’t tell which. He set his easel down loudly on the bare boards. The cat ran off. “It’s Ashlyme,” he said. He went from room to room looking for her. They were full of paintings propped up against the neutral cream walls. He found himself staring down into a square garden like a cistern, full of darkness and trailing plants. “I’m here,” he called—but was he? She made him feel like a ghost, swimming idly around waiting to be noticed. He opened what he thought was a cupboard but it turned out to be a short hall with a green velvet curtain at the end of it, which gave on to her studio.

Starting Scenes

A Storm of Wings follows the plot template of its predecessor The Pastel City. A group of adventurers is assembled and dispatched by queenly fiat to some miserable place. After traveling over the wasteland to reach their destination, they find something horrible there, and struggle with that horror.

Wings differs from Pastel in that the story doesn’t end out there at the edge of the waste. It returns to Viriconium, and introduces a new — extremely short-lived — POV character. To ease this transition, Harrison gives us some (re)establishing shots of the city.

Midwinter clutches the Pastel City, cold as thought.

In the Cispontine Quarter the women have been to and fro all day gathering fuel.

Much like a screenwriter, Harrison likes to establish setting and time of day quickly, often in the first line or two. As proof, let’s stay right where we are in the Cispontine Quarter but hop back a few chapters; this description lead off Chapter 2:

Autumn. Midnight. The eternal city. The moon hangs over her like an attentive white-faced lover, its light reaching into dusty corners and empty lots. Like all lovers it remarks equally the blemish and the beauty spot— limning the iridium fretwork and baroque spires of the fabled Atteline Plaza even as it silvers the fishy eye of the old woman cutting fireweed and elder twigs among the ruins of the Cispontine Quarter, whose towers suffered most during the War of the Two Queens.

Indeed these women are still cutting firewood in midwinter, though pickings are getting slim.

By afternoon they had stripped the empty lots to the bare hard soil, bobbing in ragged lines amid the sad induviate stems of last year’s growth, their black shawls giving them the air of rooks in a potato field. Not an elder or bramble is left now but it is a stump; and that will be grubbed up tomorrow by some enterprising mattock in a bony hand. At twilight, which—exhaled, as it were, from every shattered corner—comes early to the city’s broken parts, they filled the nearby streets for half an hour, hurrying westwards with their unwieldy bundles to where, along the Avenue Fiche and the Rue Sepile, Margery Fry Road and the peeling old “Boulevard Saint Ettiene,” the old men sat waiting for them with souls shrivelled up like walnuts in the cold. Now they sit by reeking stoves, using the ghost of a dog rose to cook cabbage!

As David Wain’s They Came Together observed, the worst of all writerly statements is “The city is like another character in this story!”

That said, Harrison engages with the idea of this city more seriously than he does with many of the human puppets. We see it in every light, every season.

Cabbage! The whole of the Low City has smelt of this delicacy all winter. It is on everyone’s breath and in everyone’s overcoat. It has seeped into the baize cloth of everyone’s parlour. It has insinuated itself into the brickwork of every privy, coagulated in alleys, hung in unpeopled corners, and conserved its virtues, waiting for the day when it might come at last to the High City. This evening, like an invisible army, it filtered by stages along the Boulevard Aussman, where it woke the caged rabbits in the bakers’ backyards and caused the chained dogs to whimper with excitement; flowed about the base of the hill at Alves, investing the derelict observatory with an extraordinary new significance; and passed finally to the heights of Minnet-Saba, where it gathered in waves to begin its stealthy assault on the High Noses. On the way it informed some strange crannies: inundating, for instance, a little-used arm of the pleasure canal at Lowth, where its spirit infected incidentally a curious tragedy on the ice.

Viriconium has some of T.S. Eliot’s DNA in it. The above paragraph reminded me of one other from Harrison, and then a stanza from “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”. First, the Eliot.